As Irish sport was imbued with the freedom that followed the repeal of the GAA's 'Ban' in the early 1970s, Con Houlihan's radical approach to the writing of his sports columns captured the urgency of this unexplored new landscape.

It was just as a new wave of British sports writers were finding their voice that Brian Glanville, a sports columnist with The Sunday Times, confronted the industry’s inability to strike the right note.

“British sports journalism is still looking for an idiom,” he claimed in 1965, “still waiting for the columnist who can be read by intellectuals without shame and by working men without labour.

A polemic spread across the pages of Encounter magazine, the deficiencies of British sports-writing were exacerbated, or perhaps only apparent, because of an American counterpart that had located its idiom some decades earlier.

“The American sportswriter,” he explained, “has never had this problem, precisely because, in a more fluid society, the idiom lay close at hand. Thus, it was possible for Ring Lardner, a serious artist as well as a journalist, to take that idiom and do something quite new with it, in creative terms.”

Arbitrarily understood as the highs and lows of a culture - Beethoven on one hand and Babe Ruth on the other - the American could present the widespread appeal of the latter through a prism of the former’s gravitas. The Briton, by comparison, was restricted by social divisions and the inhibiting notion of a class structure.

Yet, in Perry Meisel's fascinating The Myth of Popular Culture, he argues that an anxiety about what the Briton is up to that has motivated American culture. Brian Glanville fretting over what the American can do only serves to show that this apprehension goes both ways.

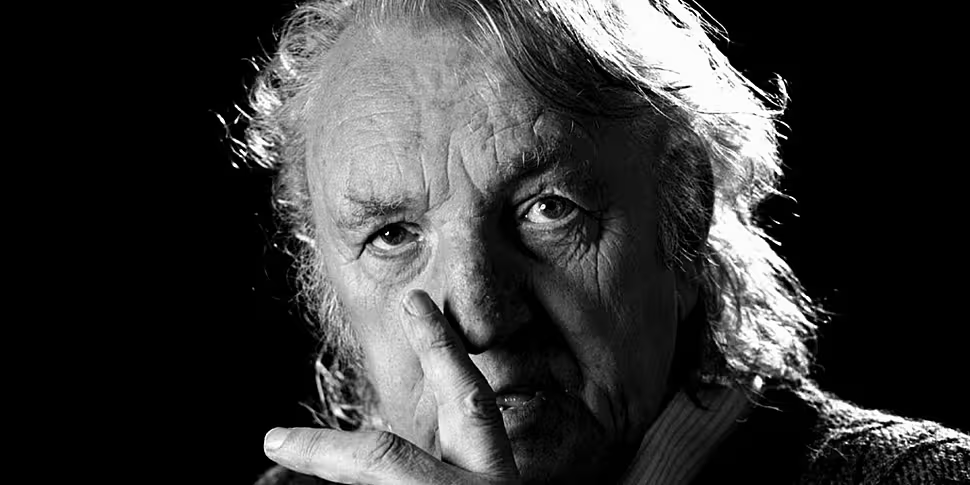

4 December 2005; Con Houlihan. Picture credit: David Maher / SPORTSFILE

4 December 2005; Con Houlihan. Picture credit: David Maher / SPORTSFILEMeanwhile, Ireland has served as a welcome refuge for the products of this ongoing cultural exchange.

If we consider sports journalism on this island at the moment of Glanville's lament, Irish sports writers would have more readily erred on the side of British formalism over the exceptionalism of its American counterpart.

After all, before the repeal of ‘the Ban’ in 1971, the GAA did a better job than most British institutions of clearly defining what sporting endeavours were acceptable for whom. It was only in its absence that Irish sports-writing may be said to have finally delivered a columnist capable of locating an idiom of this nation’s own.

"It isn't long since every village had its Joe McCarthy," wrote Con Houlihan of the Ban's 'mesmerising ignorance' and its surveillance team. "It is an astonishing fact that now (1989) on the run-in to the 21st century we still have people in our midst who are convinced that if you play Rugby or Soccer you are an inferior Irishman."

The prerequisite for Con Houlihan’s pioneering role in the development of Irish sports writing was his willingness to engage sport without prejudice. A Kerry native who made no secret of his fandom, such personal preferences merely shaped the dialogue. Dogmatism was to be avoided at all costs.

"If you asked me to name mankind's greatest curse, I wouldn't hesitate," he wrote. "I would like to bury nationalism at a crossroads and drive a stake through its heart. Now read on ..."

C. L. R. James, the Trinidadian writer responsible for writing the best sports book perhaps ever written, Beyond A Boundary, considered himself fortunate to have experienced Britain by way of ‘the working people of the North, and not the overheated atmosphere of London.’

Born in Kerry only a few years after the Irish War of Independence, Con Houlihan’s introduction to the nexus of British imperialism was, like James’, somewhat fortuitous.

“In his youth [my father] had worked in the Welsh coalfield,” recalled Houlihan in a later article. “He learned to love the miners – and the Welsh people in general. From listening to him, I began to believe that the Irish were not the only great people in the world.”

Without fear or suspicion of the outsider, Houlihan reversed Ireland's position as a receptacle for the best and worst of British and American culture. He engaged in a cultural exchange of his own.

Although his references to Thomas Hardy, James Joyce or Walt Whitman confirm that he was a voracious reader with a keen understanding of when to deploy a killer line, Houlihan's ability to construct the narrative around this moment was immense.

Consider this recollection of an appearance George Best put in for Cork Celtic over Christmas 1975:

And so the greatest gaggle of small boys and indeed small girls seen at large since the Pied Piper of Hamelin turned debt-collector. The winding little lane that leads down from the city to Flower Lodge was almost bursting its banks. I find it hard to forgive George Best for his display that day. Lo and behold - George was back for the next match (against Shelbourne at Harold's Cross). A big crowd came to that game too - and went away less than gruntled. George appeared one more time for Celtic - and people stayed away just because his name was on the teamsheet. An old truth has been illustrated - you don't pay twice to see the same fat man in the circus sideshow.

Although Houlihan’s eloquent but occasionally flowery style of writing was somewhat twee at times, his ability to harness the implicit accessibility of sport and shoot it through unexpected avenues was fresh, fearless and, critically, widely relatable.

If we allow that the American sportswriter's speciality sport is boxing, it was on the subject of horse racing that Houlihan’s writing truly came alive, however. A reliable meeting place for society’s ‘haves and have-nots’, the racecourse served as a reliable metaphor for his own work.

Be it in Cheltenham, Aintree or on an outing to the Irish Grand National with ‘carrier bags bulging with giant flasks and great parcels of sandwiches’, Con Houlihan saw it all.

Although he is now fondly remembered for suggesting that he’d missed the excitement of Italia ’90 on account of being in Italy at the time, he regularly inverted this sensation in his columns from the racecourse.

The Gold Cup success of Dawn Run at Cheltenham in 1986 was one such instance:

When Arkle stormed up the hill to his first Gold Cup, few of his myriad admirers realised that nibs of snow had started to come with the wind; yesterday it was very cold in the Cotswolds but in retrospect most of those who were on Cheltenham’s racecourse will remember the time between about half past three and four o’clock as a fragment of Summer. Such was the enormous outburst of emotion that for a little while the thin wind seemed not to matter. And no doubt there are decent men and women who will dip into their imaginations at some distant date and say that they were there – and they will be right.

Houlihan's understanding of the many ways that a horse could inspire the affections of Irish people was crucial to the success of such dispatches.

"It used to be said that the cow was the peasant's wife and the horse was his mistress," he wrote ahead of the 1981 Epsom Derby won by Shergar. The horse, capable of fulfilling roles pertaining to the livelihoods and entertainment of his various readers, was afforded the status of any great sportsperson; without ever compromising its humble origins.

"Over a few glasses of wine I try to express Shergar's impact," he recalled of a conversation struck up on the flight home. "One thinks of him as almost a different species - as Muhammad Ali looked at his peak and as Pele did that day in Mexico City when Brazil swamped Italy in the final of the World Cup.

"The two hundred and second Derby may not have been thrilling in the ordinary sense - but there is a thrill in beholding greatness."

Akin to a number of his high-profile counterparts, Con Houlihan couldn't but be enamoured by the greats. Yet, to paraphrase Bob Dylan, he never appeared too impressed.

"Although Houlihan is best known as a sports journalist," wrote Dermot Bolger by way of an introduction to A Harvest, "he has always had the gift to contextualise sport within the wider tapestry of the human condition, of which he is an expert."

It isn't so much that Con Houlihan located the kind of idiom Brian Glanville wrote of then, rather, he provided words for sensations that were implicitly known but proved difficult to express.

Through the clarity of his writing first and foremost, he commenced a much-needed public dialogue on matters deeply personal.

Related Articles:

16/03/20 | Book Review | "All right, they're the worst ball club ever" | Jimmy's Mets

19/03/20 | Book Review | "We was bored shitless" | Irvine Welsh's vision of football

Download the brand new GoLoud App in the Play Store & App Store right now! We've got you covered!

Subscribe to OffTheBall's YouTube channel for more videos, like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter for the latest sporting news and content.