The Lansdowne Road riot of 1995 was a seminal moment in forming my identity.

Like many other young men and women born in England, I have spent a lot of time and energy over the years espousing my Irish credentials in an English accent. I was born there, to a father from Derry and a mother born and raised in England to Irish parents.

Don't worry, we'll rattle through the tedious family history part of this pretty quickly.

My mother was the second of seven children - there wasn't much to do apart from churn out kids - and Mum was the first to not be born in Galway.

My maternal grandparents loved living in England. It gave them opportunities that were not as available as they were in 1950s Ireland. My grandmother was always talked of in almost-hallowed terms by her siblings - she was 'the smart one' that would go on to do great things. But the fact remained that the social conditions in Ireland at that time didn't allow her to do so.

Later in life, she was delighted that she was given the opportunity to buy her council house under her name.

Women were seen as primarily home-makers and domestic carers in Ireland at that time and, while many had to work out of sheer necessity, one wonders how many women of her vintage cut frustrated figures due to social conditions dictated in large part by the Catholic church.

In her eyes, these issues were of less importance in the UK. She moved to St Albans, a small Hertfordshire city, where she pursued a career as a mental health nurse. St Albans had a sizeable Irish influence, seen in even just the names of those that lived around her: the O'Dwyers and the McNicholas' being some of the family's closest friends.

My maternal grandfather was a functioning alcoholic. This was in part due to the abuse that he suffered at the hands of the church, and he was only too happy to move away when the opportunity came. In fact, in the most Irish possible anecdote, I spoke to a taxi driver in Galway last year who recognised the family resemblance. It turned out that Grandad had brought this guy over to St Albans as a labourer in the early 1970s and they settled there too.

Hopefully that jaunt down memory lane wasn't too painful, but my family's story is but a small volume in the library of Irish-English migration.

Lansdowne Road - 25 years on

Two generations on, I find myself a man without a country.

My father is a proud nationalist from Derry, but not an outright Republican. The 1970s pub buckets being handed around for the 'RA were not something he sought out, and 'Tiocfaidh ár lá' was not something that was said by him or his four brothers.

They'd seen too much.

What growing up in the Troubles did do, however, was form a kindness and decency in them that prevails to this day, and an outright aversion to the bombast of violence.

It was being brought up by such people that I sat down to watch Ireland v England in 1995. I was obsessed with football and was looking forward to seeing two teams close to my heart play the game that I love. In all honesty, your national identity is not something you think of as a 9-year-old. I had watched World Cup '94 with my family in Ratoath, and was bouncing around to Ray Houghton's lob over Pagliuca with all my cousins. I loved Ireland - I loved England too.

What I saw at Lansdowne I still remember for the contrast with the kind of moments I associate with Houghton and Ireland. It became abundantly clear early on that there was crowd trouble, and that it was the England fans causing it. It was not something that I had seen in any great detail before as media organisations were loathe to show it.

Not that day. The images we recognise now were played out, in real-time, to a worldwide audience.

My identity changed that day but, thanks to the decent English and Irish people I had around me, I didn't lurch from being a hooligan to becoming avowedly anti-England. I was surrounded by people on both sides that were good, hard-working people that wouldn't have allowed either. They cared for their families and knew that what I was seeing on screen was not indicative of the majority of England fans.

In my school playground in St Albans, not many kids were throwing classroom furniture around, singing 'No Surrender to the IRA'.

The future

The reality is that most England fans then were decent people, ashamed by the dickheads who do such things. Most fans would revel in England's good performances and loved to moan when things don't go their way. That goes for every country, including Ireland.

At no point did that hooliganism represent what I thought supporting England to be. What I didn't realise at the time was that we were witnessing the embers of a cultural identity for some England fans who revelled in the violence and chaos. Chaos that they exported.

These were sad people. Parenting being what it is, part of the problems that we see in current fan culture are due to their kids now going to matches and aping what they saw.

For a long time after that match, I felt a draw to Ireland and Irish matches - that is still the case. I don't mind people calling me a 'Tan' (naming no names in the Off The Ball offices) - it will always be that my mates in England think of me as Irish and those here hear the accent and make a judgement. But, in reality, it doesn't really matter.

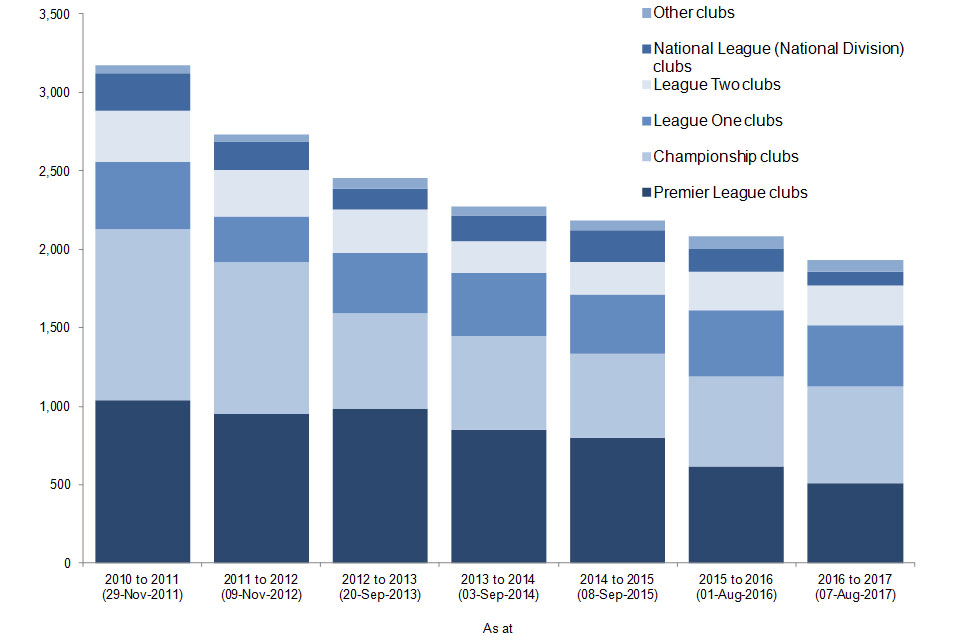

Source: Home Office, Football-related arrests and banning order statistics, England and Wales, 2016 to 2017 season, table 2.

Lansdowne Road in 1995 showed the worst sides to some England fans, but this was the apotheosis of the type of stupidity that caused horrendous problems in the 1970s and 1980s. There are still problems, but these are trending down.

We are in a fraught period of British and Irish relations, and there will always be dickheads on both sides.

The decency that I saw with family and friends that support England is still there - the same with Ireland.

We need to remember that Lansdowne Road was a low point. Ireland and England have an often awfully-toxic history. But history belongs to other people.

People do not own the wrongdoings of their forebears, nor do the acts of heroism reflect on those today that did not do them.

It is on us to keep treating people with decency and understanding, and create our own.

Ireland and England have a lot in common. A lot different, of course, but what unites the two is more than what divides us, as symbolised by the success that my family found in England, and the friends and families they made along the way.

The more that we can recognise that, and listen to the opinions of others without jumping down each other's throats, the less incidents like Lansdowne Road are likely to occur.

Download the brand new OffTheBall App in the Play Store & App Store right now! We've got you covered!

Subscribe to OffTheBall's YouTube channel for more videos, like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter for the latest sporting news and content.