“If you have good thoughts they will shine out of your face like sunbeams and you will always look lovely.”

Ian Wright has one of these faces.

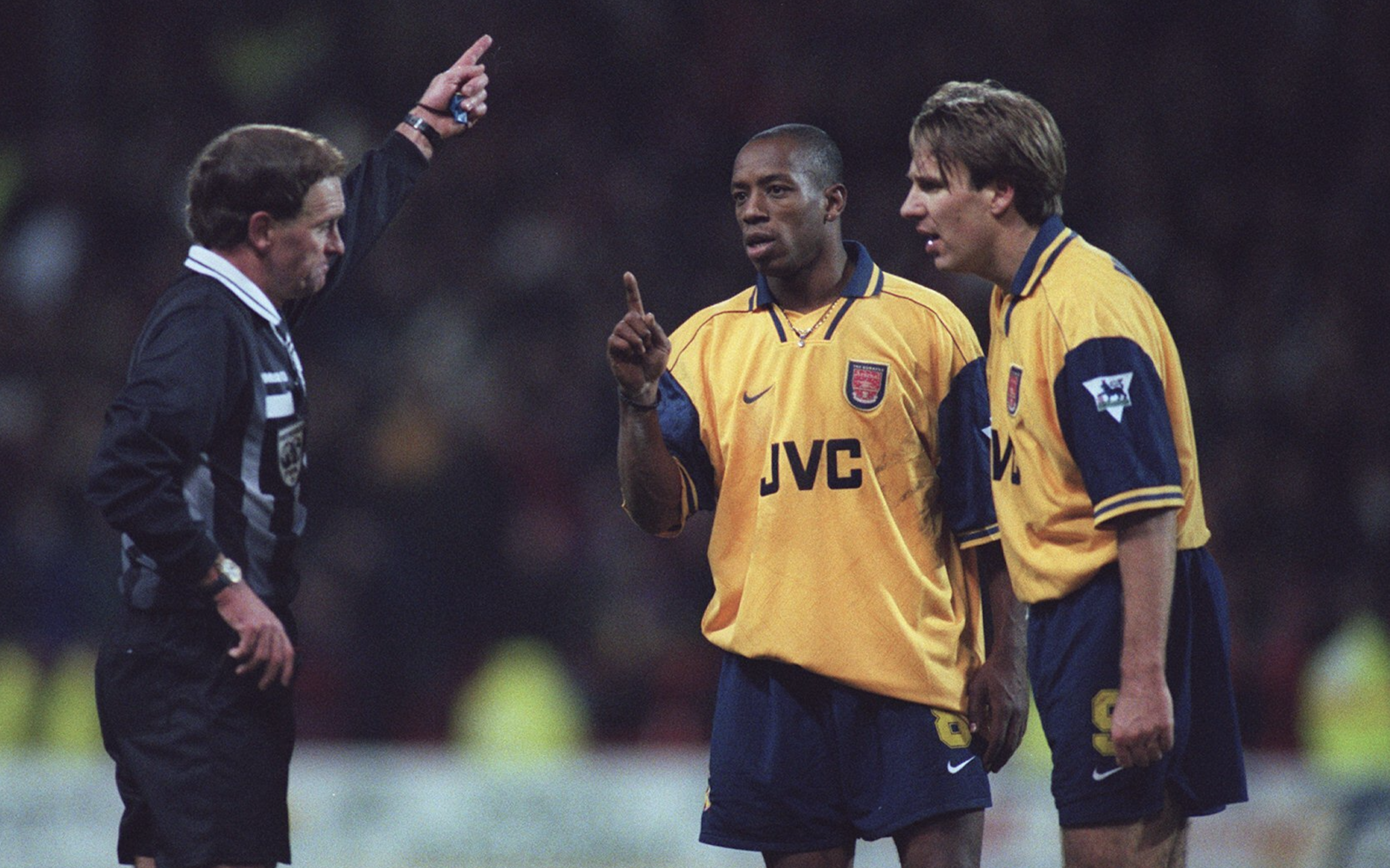

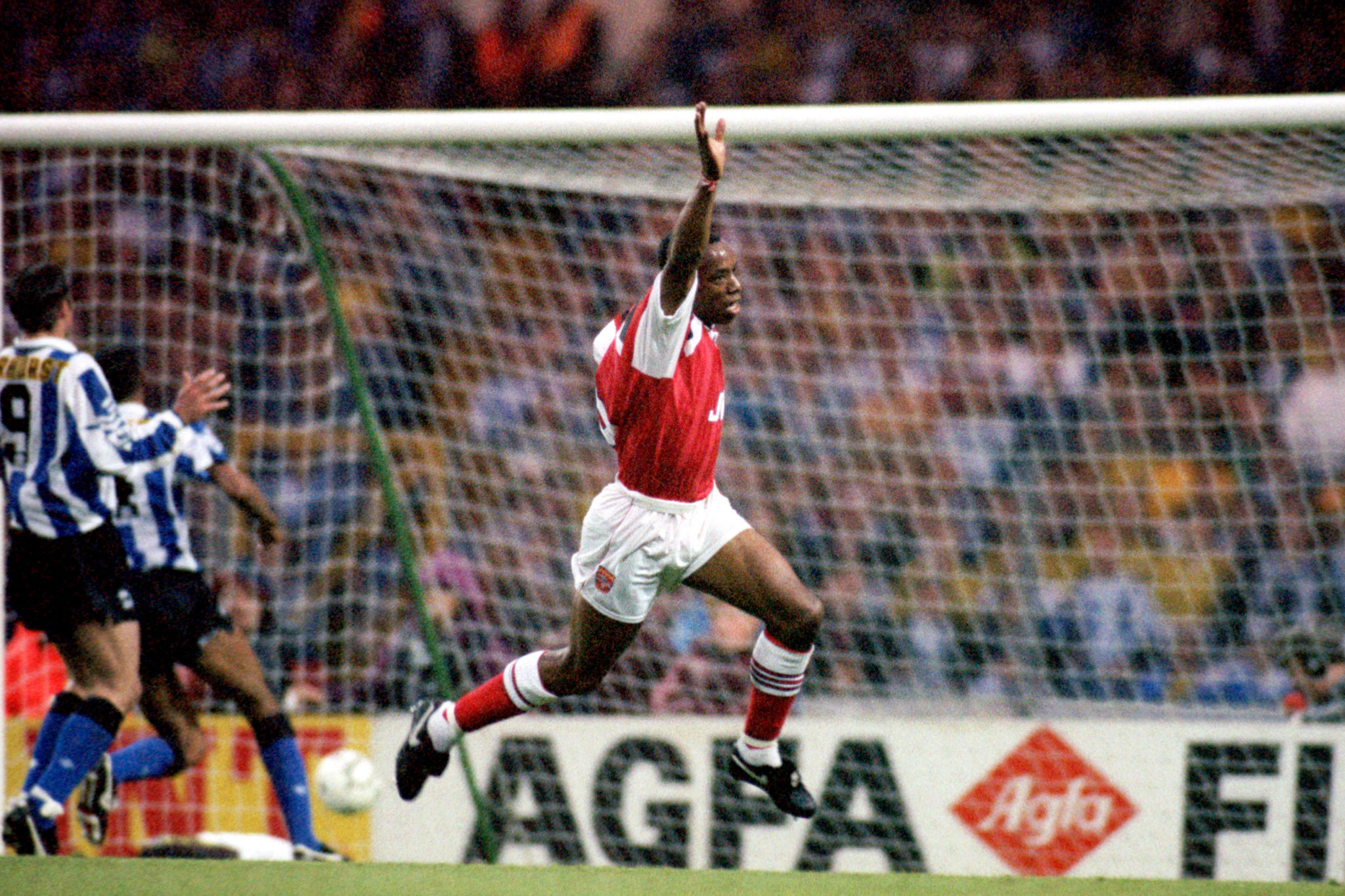

One of my mates from primary school, Tim Couch, was a Gooner. We used to knock around together a lot, and he was obsessed with Ian Wright. Cantona was my guy, but I'd always keep one eye out for Wrighty. He was one of those links to the Graham era who just got Wenger, and Wenger got him. A mix of industry and goal-bothering, those sunbeams glinting off his gold tooth.

Wrighty had that edge. The toughness that was so ingrained in the Arsenal DNA - the never-say-die attitude of Charlie George, David Rocastle, Steve Bould and the other bricks in the wall. The character that football fans miss all the more in recent Arsenal sides.

Wright would regularly get sent off for these rushes of blood to the head, lashing out at those that had crossed him. If only we'd known then.

The drinking culture of the 'Tuesday Club' at Arsenal hid the more chronic urges of the likes of Tony Adams and Paul Merson. When Adams told the Arsenal squad that he was an alcoholic, Merson famously thought 'If you're an alcoholic, what am I?'

In the same vein, the teak-tough Premiership of the mid-1990s allowed Wright to hide in plain sight, too. His violent outbursts were, in part, an inability to process a home life that was riven by domestic violence, severe emotional abuse and coercive control.

Ian Wright: Home Truths

'Home Truths', the BBC documentary of Wright and his journey into that past, could not have picked a better frontman. In addressing his own experience, Wright meets with survivors of domestic abuse, both adult and child at the time it occurred, and does what he does best. He puts people at ease, lets them take centre-stage, and listens. You can't help but feel Ian became so good at listening because young Ian must have been so desperate to be heard but too frightened to speak.

Wright's stepfather would beat his mother as a matter of routine. His brother, Maurice, would cover Ian's ears as the abuse occurred, in their single-room house in Brockley. They didn't even have a physical refuge.

One of the most heartbreaking parts of the documentary is when Wright revisits that house on Merritt Road. The animation is expertly done, showing young and old Ian going upstairs at the same time - and as he pauses to gain composure, so does the viewer. It's the kind of programme that makes you want to reach through the screen and put an arm around his shoulder.

One of the more painfully expert pieces of emotional abuse from his stepfather was when young Ian would be made to stare at the wall as Match of the Day came on. As a viewer, you're left thinking: 'you used the thing he loved the most against him, you bastard'. Who knows what professional Ian Wright felt as he tuned in to watch his goals for Palace and Arsenal, the opening bars representing so much darkness and light.

The shot lingers on Wright with his back to the wall now, explaining what happened as he keeps his feelings at arm's length. His breath catches as he half-laughs, saying 'this wall doesn't know how much it's affected my life.'

Christ.

It is a documentary that highlights the horrifying panoply of abuse. Survivors, young and old, are heard; helping and cajoling Wright along the way to not downplay his feelings. After all, just because someone had it hard as well, doesn't mean you didn't.

It is the arrival at some form of resolution that is the most beguiling, and one feels that it comes from speaking to both a psychiatrist and a former domestic abuser. He visits Dr Nuria Gené-Cos, a Trauma and Disassociation specialist, who hands him a foam-rubber ball to 'ground' him during the session.

Slowly, the boyish expression begins to change into that of the little boy as he recalls the abuse. It is heartbreaking to see the hurt, anger and shame bubble up, as adult Wright and young Ian meet in front of the lens.

It feels even a little intrusive to realise that Wright's mother would exert what Dr Gené-Cos calls 'severe emotional abuse' on young Ian. The details are not for here, but the impression you are left is of a boy with no physical or emotional refuge; he couldn't leave the room, his mum was dealing with so much that she lashed out.

Thank god, then, for Sydney Pigden.

He's a name known to a lot of football fans, but he's always worth revisiting. Mr Pigden was a primary school teacher who dedicated his life to improving those of the children of Brockley, one of London's most deprived boroughs. He proved that you didn't need to fly Spitfires against the Nazis to be a hero.

Oh, but he did that as well - just to be sure.

The video above used to be heartbreaking enough, before realising what this man must have meant to a child silently crying out for love. If his stepdad was telling Ian what he couldn't be, Mr Pigden was the one telling him, in a cajoling and encouraging voice, what he could. I doubt that Turnham Academy has ever had a more dedicated milk monitor than Ian Wright before or since.

Finally, the documentary visits the Hampton Trust, a charity dedicated in part to working with abusers to understand and change their thought patterns. We meet Wes. He could have been the Sliding Doors-version of Wright, if one gives credence to the idea that survivors either reject or repeat their experiences.

Wes and his family were abused in a way unimaginable to those reading. He recalls his mother being beaten with a motorcycle helmet that both turns the stomach and engages the brain - how was this child supposed to function properly after that? Wes said he used to fear going to school because he would be leaving his mum open to abuse - when he was there, he felt that at least he could take the brunt of it.

He went on to take this out on what could be one or multiple partners. Wes checked himself into the Hampton Trust to break the cycle. It is a triumph of the documentary to put a face to a label, and realise that abusers are not just created in a vacuum.

We're left with the stark statistic that one million children in the UK are suffering similar abuse to that of Wes and Wright. The scale of the issue makes you start relating it to your own life: who do I know whose body tightens when they get a call from their partner? Which kids act out in our kids' classes that might be crying out for attention and intervention? Where can we funnel resources to ensure that, eventually, no child goes into a fitful sleep with hands over their ears?

What is a troubling, heart-rending watch is ultimately a hopeful one. Ian Wright has gone through some of the worst experiences imaginable.

Here he is, realising he can forgive, if not forget.

Yet the sunbeams continue to shine from his face and his loveliness is there for all to see.

'Ian Wright: Home Truths' is available on BBC iPlayer.

If you are affected by any of these issues, please contact Aoibhneas, who provide domestic abuse support for women and children.

Download the brand new OffTheBall App in the Play Store & App Store right now! We've got you covered!

Subscribe to OffTheBall's YouTube channel for more videos, like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter for the latest sporting news and content.