Upon the release of two new songs by Bob Dylan, Arthur James O'Dea, taking great license with the 'Other Sports' heading of Off The Ball's website, explored why they're not half of what they've been cracked up to be.

It had been eight years since Bob Dylan released new music before the sudden emergence of “Murder Most Foul” a little over three weeks ago.

Overwhelmingly, the song was hailed as another masterful return to form for an artist who has commodified 'the comeback' more effectively than most.

“I Contain Multitudes”, another new release whose exact origin remains equally uncertain, commanded less attention but pushed the same message. Dylan’s back, again.

As excitement grows about the prospect of a new album, it appears that something in how we critically assess Dylan has changed, however. After a few years spent entertaining himself (and some listeners, admittedly) uncovering the Great American Songbook, the demands put upon the great American star and his talents are no longer what they were.

Bob Dylan has grown old. We must appreciate what we are given.

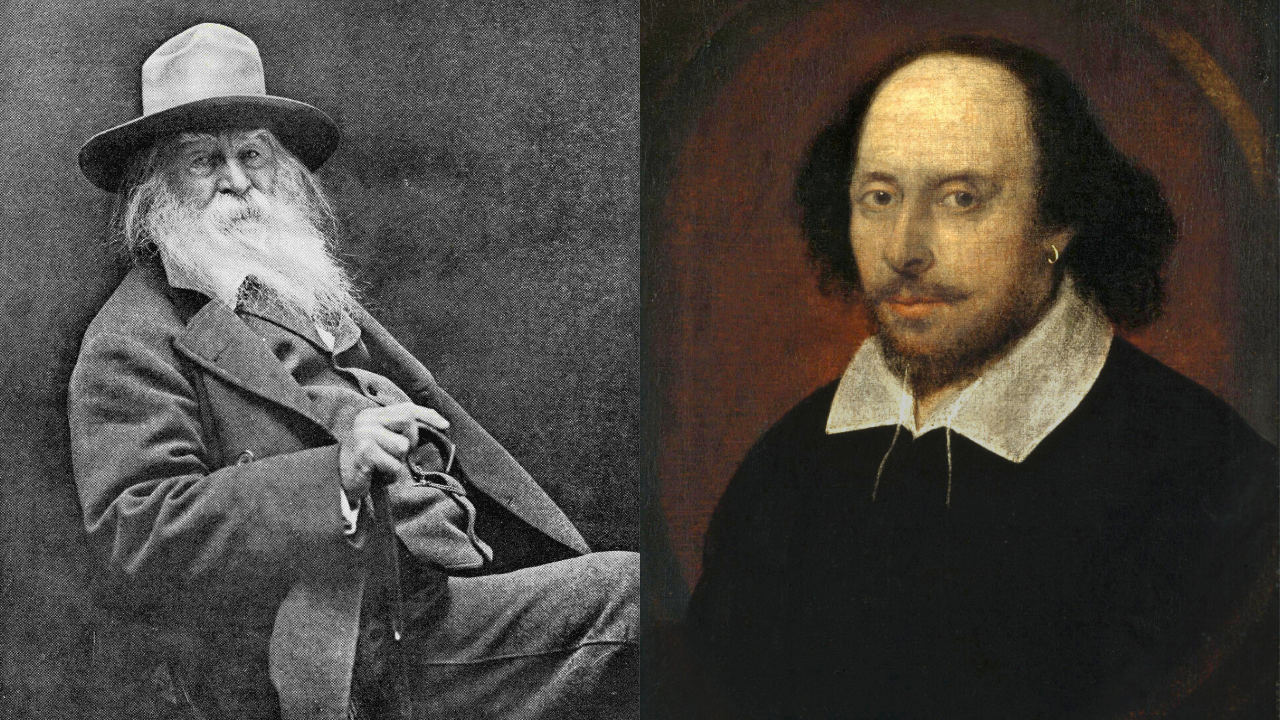

For however effusive Nick Cave and Neil Young are in their praise of “Murder Most Foul”; however thrilling the prospect of Dylan’s nods toward William Shakespeare and Walt Whitman may be with these songs’ titles; however amusing it is that a near 17 minute song became Dylan’s first #1; however welcome it was to have something fresh from an artist who again demonstrated his knack for knowing the right time to act, it is misguided to consider these songs as anything resembling his best work.

Set to turn 79 next month, it is tempting to chalk “Murder Most Foul” and “I Contain Multitudes” down to the onset of an artistic late style. As Theodor Adorno wrote of the ageing Beethoven’s creativity: “His late work still remains process, but not as development; rather as a catching fire between the extremes, which no longer allow for any secure middle ground or harmony of spontaneity.”

What else could “Murder Most Foul” be than evidence of Dylan’s inability to weave a series of cultural touchstones together into a satisfying whole? Consider his handling of such lofty themes in the similarly epic “Desolation Row” and one sees how it used to be done:

Praise be to Nero's Neptune, the Titanic sails at dawn

Everybody's shouting, "Which side are you on?!"

And Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot fighting in the captain's tower

While calypso singers laugh at them and fishermen hold flowers

Between the windows of the sea where lovely mermaids flow

And nobody has to think too much about Desolation Row.

Whereas with “Murder Most Foul”:

You got me dizzy, Miss Lizzy

You filled me with lead

That magic bullet of yours has gone to my head

I'm just a patsy like Patsy Cline

Never shot anyone from in front or behind

I've blood in my eye, got blood in my ear

I'm never gonna make it to the new frontier

Zapruder's film I've seen that before

Seen it 33 times, maybe more

It's vile and deceitful

It's cruel and it's mean

Ugliest thing that you ever have seen

They killed him once and they killed him twice

Killed him like a human sacrifice.

All of the basic elements are there, but no synthesis is achieved.

Over the course of almost 17 minutes, as he references a variety of artists, songs and more, it also becomes clear that where he once had the good creative sense to rein in what wasn’t necessary, we are now left with this flabby mess of a song.

In time, “I Contain Multitudes” will likely fade into the shadowy depths of Dylan’s back catalogue. “Murder Most Foul” though, this will remain too tempting for a number of fans to just discard. Furthermore, Bob Dylan knows it.

The inspiration of an unshakeable faith, much of the scholarship surrounding Bob Dylan’s work winds up in the same pit of despair.

For the fundamentalists – or the Dylanologists, as David Kinney’s study labels them – the rabid search for meaning in his lyrics, album covers, or any aspect of his expression is exhaustive. Thankfully, unless you go seeking them out, those who worship at the altar of Dylan tend to bother only one another.

Dwelling closer to the surface, however, are those listeners for whom Dylan remains a symbol of something beautiful in their past.

Akin to the “gibbering hippies” of the Swedish academy that Irvine Welsh scolded after Dylan was awarded his Nobel prize for literature, this section of the faithful remain powerful by virtue of their number. Crucially, age presents no barrier for your right to feel nostalgic.

With their overwhelming penchant for Dylan’s earlier works, it is with these fans that the agenda for what ‘Bob Dylan’ is and what he represents is publicly set.

“No matter what Bob Dylan has done in the last forty-seven years,” surmised the esteemed Dylan scholar Greil Marcus around a decade ago, “or what he will do for the rest of his life, his obituary has already been written. ‘Bob Dylan, best known as a protest singer form the 1960s, died yesterday …’ The media loves a simple idea.”

By and large, the same can be said of Dylan’s fans.

Is it any great wonder then that a song built upon the assassination of President John F. Kennedy should strike the right note for so many of Dylan’s ardent listeners?

This song is a study in lost potential. Where we knew that the Titanic would sink in “Tempest”, and that the retelling of John Lennon’s brutal murder in “Roll On John” came after the former Beatle’s legacy was secured, “Murder Most Foul” dwells on what could have been; be it the song itself or even, perhaps, on what you could have been.

Whether he has ever possessed the singular influence to shift the direction popular music is going as has been written of him is unclear. Either way, Bob Dylan’s ability to read a moment in time and act decisively is unquestionable.

“This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back,” wrote Dylan of “Murder Most Foul” to his fans, “that you might find interesting.”

Far from inspiring a renewed faith in Bob Dylan’s creative genius, “Murder Most Foul”, a song that in all likelihood proved one epic too far for Tempest, is the rough draft of a story that has already been told.

Do not mistake it for nostalgia on the artist’s part though, this one was really for the followers. Something to gush over, something to query, a song that requires little work to gather what is going on. A time of great uncertainty, sure, but at least you know how it will all play out.

Bob Dylan is getting old, but it is the fans who are ageing.

Download the brand new GoLoud App in the Play Store & App Store right now! We've got you covered!

Subscribe to OffTheBall's YouTube channel for more videos, like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter for the latest sporting news and content.